Malik Siraj Akbar, Editor in Chief of The Baloch Hal, is known for his flattery of the bold and the beautiful, ie. the rich, powerful elites of Pakistan. In the past he has been seen flattering Akbar S. Ahmed and Husain Haqqani. Now he has broken his own record of flattery by describing Najam Sethi as the most trusted man in Pakistan. Here are relevant xcerpts from Malik Siraj Akbar’s flattering piece on Najam Sethi in the Huffington Post:

Pakistan’s Walter Cronkite Heads the Regional Government

Written by Malik Siraj Akbar

Editor in Chief, ‘The Baloch Hal’

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/malik-siraj-akbar/pakistans-walter-cronkite_b_2989118.html

[PPP and PML-N have] picked up a veteran journalist with an unquestionable integrity to take care of the affairs of the government for the next two months.

Mr. Sethi is the founder of the Lahore-based liberal weekly, the Friday Times, and a popular talk-show host on Geo News, the nation’s first private news channel. His nonpartisan and accurate analyses on television have made him the equivalent of Pakistan’s Walter Cronkite, who was popularly known as “the most trusted man in America.” Mr. Sethi’s appointment is perhaps flatteringly the highest recognition of his impartiality.

Conservatives and hyper-nationalists have frequently expressed resentment to Mr. Sethi’s liberal views. They describe him too pro-west and critical of the Pakistani Taliban. In 1999, the powerful Directorate of Inter-Service Intelligence (I.S.I.) kidnapped him for what the state officials billed as a ‘controversial’ and “anti-Pakistan” speech he delivered in India. Recently, Mr. Sethi was once again threatened with death warnings which compelled him to flee to the United States where he temporarily undertook a fellowship at the New America Foundation in the Washington D.C. He returned to Pakistan only after publicizing the threats. While in Pakistan, Mr. Sethi aired his popular talk-show from a small studio established inside his house because he did not apparently consider driving from home to office a safe option.

Besides the professional integrity part, the appointment of Mr. Sethi also reflects the broader changing dynamics of the Pakistani news media. Since General Musharraf, the military ruler from 1999 to 2008, liberalized the media a decade ago, the news media has deeply influenced the society and politics in Pakistan. While some talk-show hosts, such as Mr. Sethi, have established themselves as highly credible, the others have become the agents of promoting conspiracy theories and instilling dangerous sentiments of hyper-nationalism among their viewers.

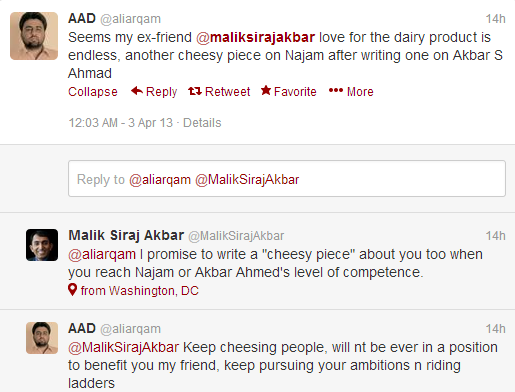

Reaction on Pakistani’s social media